دبي،22-07-2025(QW): – لطالما ارتبطت القهوة ببدايات اليوم حول العالم، فهي المشروب الذي يعوّل عليه الملايين لليقظة والانطلاق. لكن دراسة أمريكية جديدة تدق ناقوس الحذر، كاشفة عن علاقة معقدة ومتباينة بين استهلاك القهوة ومستويات الدهون في الدم، والتي تُعد من أبرز عوامل الخطر المؤدية لأمراض القلب.

الدراسة، التي أجراها باحثون من جامعة تشنغدو للطب الصيني التقليدي، حللت بيانات ما يزيد على 12,000 شخص بالغ من المشاركين في “المسح الوطني للصحة والتغذية” (NHANES) في الولايات المتحدة بين عامي 2005 و2020. وقد نُشرت نتائجها في مجلة Frontiers in Nutrition الرصينة، لتكشف عن صورة مزدوجة لتأثير القهوة على الصحة القلبية.

بين النفع والضرر: توازن هش داخل الفنجان

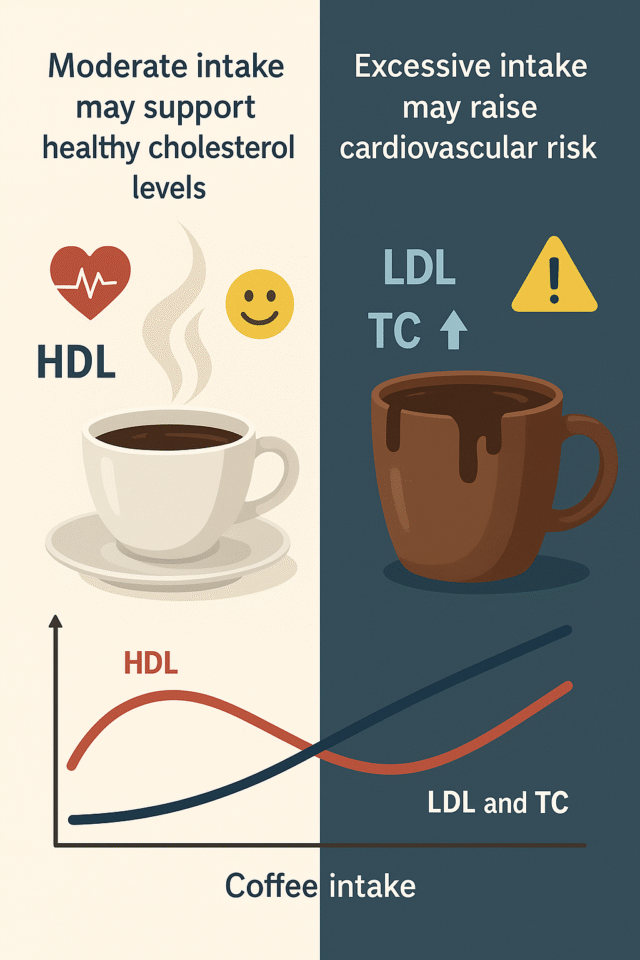

أظهرت الدراسة أن القهوة ليست بريئة تمامًا كما قد يُخيّل للبعض. فبينما أظهرت بعض الفوائد المرتبطة برفع مستوى الكوليسترول الجيد (HDL)، كشفت أيضًا عن زيادات واضحة في الكوليسترول الكلي (TC) والكوليسترول الضار (LDL) مع ارتفاع معدلات الاستهلاك.

فكل كوب إضافي من القهوة يوميًا ارتبط بزيادة قدرها 1.23 ملغم/ديسيلتر في الكوليسترول الكلي، و1.22 ملغم/ديسيلتر في الكوليسترول الضار. أما من يتناولون 3 أكواب فأكثر في اليوم، فقد سجلوا زيادات أكبر بلغت 8.45 ملغم/ديسيلتر للكوليسترول الكلي، و7.86 ملغم/ديسيلتر للكوليسترول الضار، مقارنةً بمن لا يتناولون القهوة إطلاقًا.

تأثير يختلف بين الرجال والنساء

تميّزت هذه الدراسة بتركيزها على الفروقات البيولوجية بين الجنسين. ففي النساء، لاحظ الباحثون ارتفاعًا في الكوليسترول الجيد (HDL) مع استهلاك القهوة حتى حد 2.6 كوب يوميًا، ليتراجع بعد ذلك في منحنى عكسي على شكل حرف U. أما في الرجال، فكان النمط المشابه يتعلق بالدهون الثلاثية (TG)، إذ ارتفعت مع استهلاك القهوة حتى 3 أكواب يوميًا، ثم بدأت بالتراجع.

وفي حين استقرت مستويات الكوليسترول في الرجال بعد تجاوز 5.3 و6.4 أكواب يوميًا، لم تُسجل هذه الظاهرة لدى النساء، مما يشير إلى احتمالية وجود دور هرموني – مثل تأثير التستوستيرون المضاد للالتهاب – يمنح الرجال مقاومة أكبر لبعض التأثيرات السلبية للقهوة.

ما الذي يجعل القهوة ترفع الكوليسترول؟

يعزو الباحثون التأثيرات السلبية لزيادة الكوليسترول إلى مركبات تُعرف بالديتيربينات، وعلى رأسها “كافستول” و”كاهويول”، والمتوفرة بكثرة في القهوة غير المُفلترة. هذه المركبات تُعيق نشاط مستقبلات الكبد للكوليسترول، وتُقلل من إنتاج الأحماض الصفراوية، مما يؤدي إلى تراكم الكوليسترول في الدم.

أما الارتفاع في الكوليسترول الجيد عند استهلاك القهوة بكميات معتدلة، فقد يكون ناتجًا عن تحفيز عمليات التمثيل الغذائي، لكنه يتراجع لاحقًا بسبب تأثيرات التهابية تنجم عن الإفراط في الاستهلاك. فقد أظهرت دراسات سابقة أن تناول القهوة بكميات عالية يرتبط بزيادة في مؤشرات الالتهاب مثل البروتين التفاعلي C وإنترلوكين 6، وهي عوامل من شأنها تقليل مستوى HDL في الدم.

عوامل ناقصة… وتحذير واجب

ورغم ثراء التحليل، تُشير الدراسة إلى بعض الجوانب التي لم تُغطَّ، مثل طريقة تحضير القهوة (مفلترة أم لا)، ونوع الإضافات المستخدمة (سكر، كريمة، حليب)، وتأثير الكافيين في مقابل القهوة منزوعة الكافيين. هذه العوامل، التي لم تُفصّل بسبب نقص البيانات، قد تلعب دورًا مهمًا في تحديد التأثير النهائي على دهون الدم.

ما الرسالة التي تقدمها هذه الدراسة؟

إن هذه النتائج لا تعني التوقف عن تناول القهوة، بل توضح أن الاعتدال هو المفتاح. فكوب إلى كوبين في اليوم قد يحمل فوائد، لا سيما لدى النساء، في رفع الكوليسترول الجيد وتحسين التوازن العام للدهون. أما الإفراط، لا سيما ما يتجاوز 3 أكواب يوميًا، فيرتبط بزيادة في الكوليسترول الضار، وقد يُفاقم من خطر الإصابة بأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية، خاصةً لدى من يعانون من عوامل خطر أخرى.

لماذا تُعد هذه الدراسة مرجعية؟

تتميّز الدراسة بكونها واحدة من أكثر الدراسات شمولًا واعتمادًا على بيانات وطنية أمريكية تمتد لـ15 عامًا، مستخدمةً تحليلات إحصائية متقدمة تشمل الانحدار المتعدد وتحليل المنحنيات غير الخطية. كما تُعد من القلائل التي تناولت الفروقات بين الجنسين في العلاقة بين القهوة والدهون.

الخلاصة: فنجان القهوة… متعة محسوبة

يبقى لفنجان القهوة سحره، لكن مثل كل شيء، فإن الإفراط في تناوله قد ينقلب إلى ضرر. إن كنت من عشاق القهوة، فاعلم أن الاستهلاك المعتدل لا يزال آمنًا – بل مفيدًا في بعض الحالات – ولكن تذكّر أن تجاوز الحد قد يفتح بابًا على مخاطر صحية صامتة لا تظهر إلا لاحقًا.

لقراءة الدراسة الأصلية كاملة (بالإنجليزية)، اضغط هنا:

🔗 Coffee Consumption and Serum Lipids – Frontiers in Nutrition