A brief history of coffee in Russia

For the first time, our compatriots tasted coffee during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich … and were dissatisfied! Loved by many nowadays, the drink was drunk reluctantly four centuries ago, like a bitter medicine. A European doctor prescribed coffee for the tsar “from the main disease”, and the miraculous decoction, apparently, helped to cope with severe migraine.

Coffee versus vodka

The first Russian ruler who “tasted” coffee was Peter the Great. During the opening of the Kunstkammer in 1714, he ordered “… not only to let everyone here for free, but if anyone comes with a company to see rarities, then treat them to a cup of coffee or a glass of vodka at my expense…”. Alas, it is not known for certain which of the visitors chose the “white”, and who – a foreign drink. The sovereign himself became addicted to coffee during the Great Embassy, when he was visiting the Mayor of Amsterdam Nicolaas Witsen. By the end of the XVII century, the Dutch owned coffee plantations in their colonies in Java, Sumatra and Ceylon. That is why throughout the XVIII century coffee came to Russia from Holland. Peter I liked to shock his entourage by suddenly appearing at their house with a demand to urgently pour him a cup of hot coffee, but not everyone could please the sovereign. The first coffee houses in St. Petersburg opened already at the end of Peter’s reign. In 1724, by decree of the emperor, fifteen taverns appeared in the capital, whose visitors (mostly foreigners) were served coffee.

In the era of palace coups, coffee became the drink of the Russian aristocracy. The attitude towards him, however, was still ambiguous. The poet Antiochus Cantemir, for example, called coffee “the swill that India sends”, but at the same time he understood the varieties of “swill” well: “We all know that that vegetable, fried, finely ground and boiled in water, serves instead of breakfast, and whimsical and fun after lunch. The best coffee comes from Arabia, but in all the Indies that vegetable is abundant.” By “Indies” Cantemir meant the East and West Indies (Brazil). By the way, Europeans in those years also treated the drink in two ways: the British, French and Dutch enjoyed its taste, and the Germans banned consumption – sometimes even legally.

Interestingly, Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst, who arrived from Prussian Stettin (she is the future Catherine II) unlike her fellow countrymen, she adored coffee and could drink up to five cups in the morning. The empress brewed the drink on her own – contemporaries claimed that a rare person would have liked such strong coffee. During the reign of Catherine the Great, fortune-telling on coffee grounds became a popular entertainment of the aristocracy.

A delight for the nobility

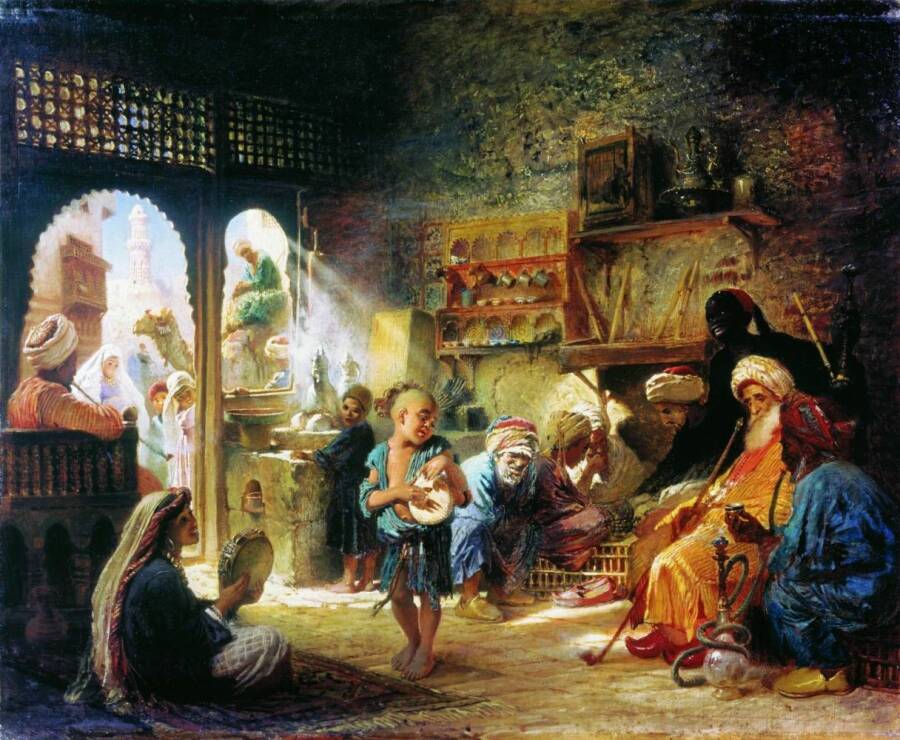

Throughout the XVIII century, coffee remained a drink “for the elite”. In 1791, when signing the Iasi Peace, the Russian delegation received a diplomatic gift from the Turks: 37 pounds of coffee and jewelry. The vast majority of the inhabitants of the Russian Empire at that time did not even know about coffee. The drink did not “go out” for a long time beyond the noble salons and a few restaurants. Everything changed during the Napoleonic Wars. When in 1805 the Russian troops were in Austria, the soldiers saw that the local population was consuming an unknown drink. The standard-bearer of the 2nd Moscow Musketeer Regiment, Ivan Butovsky, said that the soldiers nicknamed Austrian coffee “kava” and slurped it with a spoon from large plates – just like cabbage soup.

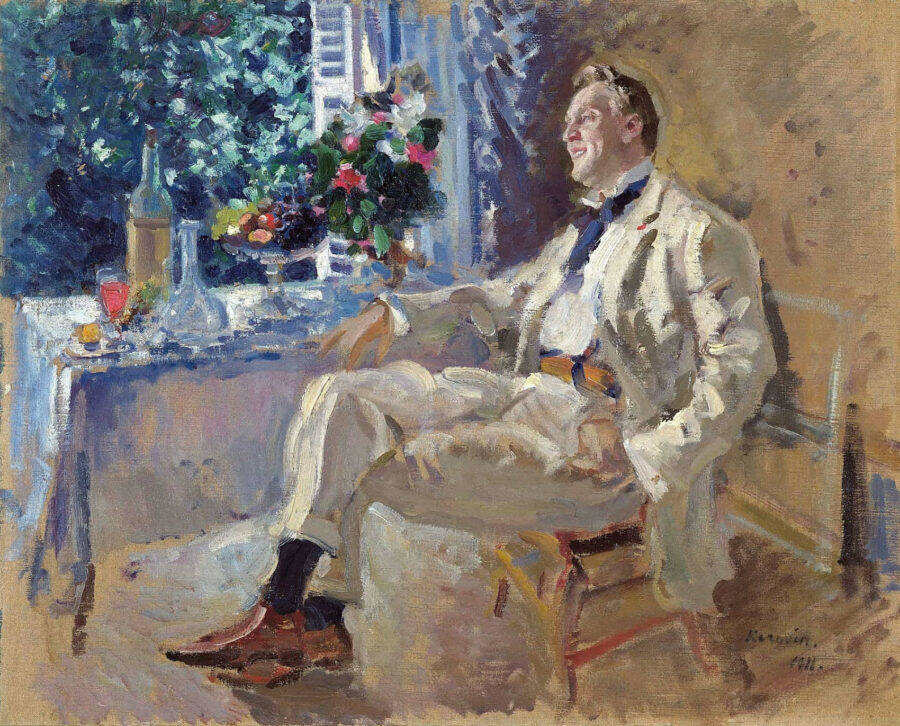

In the Russian Empire of the XIX century, the most expensive Arabian coffee cost 30 rubles per pood, and cheap Brazilian coffee cost about 17 rubles. He did not make a serious competition for tea. At the beginning of the twentieth century, imports between these drinks differed tenfold. Coffee did not become a popular drink, but it fell in love with representatives of the nobility and creative intelligentsia. Opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin recalled that he tried coffee at the age of 16, when he worked as a scribe in court: “Here for the first time I experienced the pleasure of drinking coffee – a drink unknown to me until that time. They gave coffee with cream for a nickel per glass. I received a salary of 15 rubles and, of course, could not enjoy coffee every day…”.

Difficult times

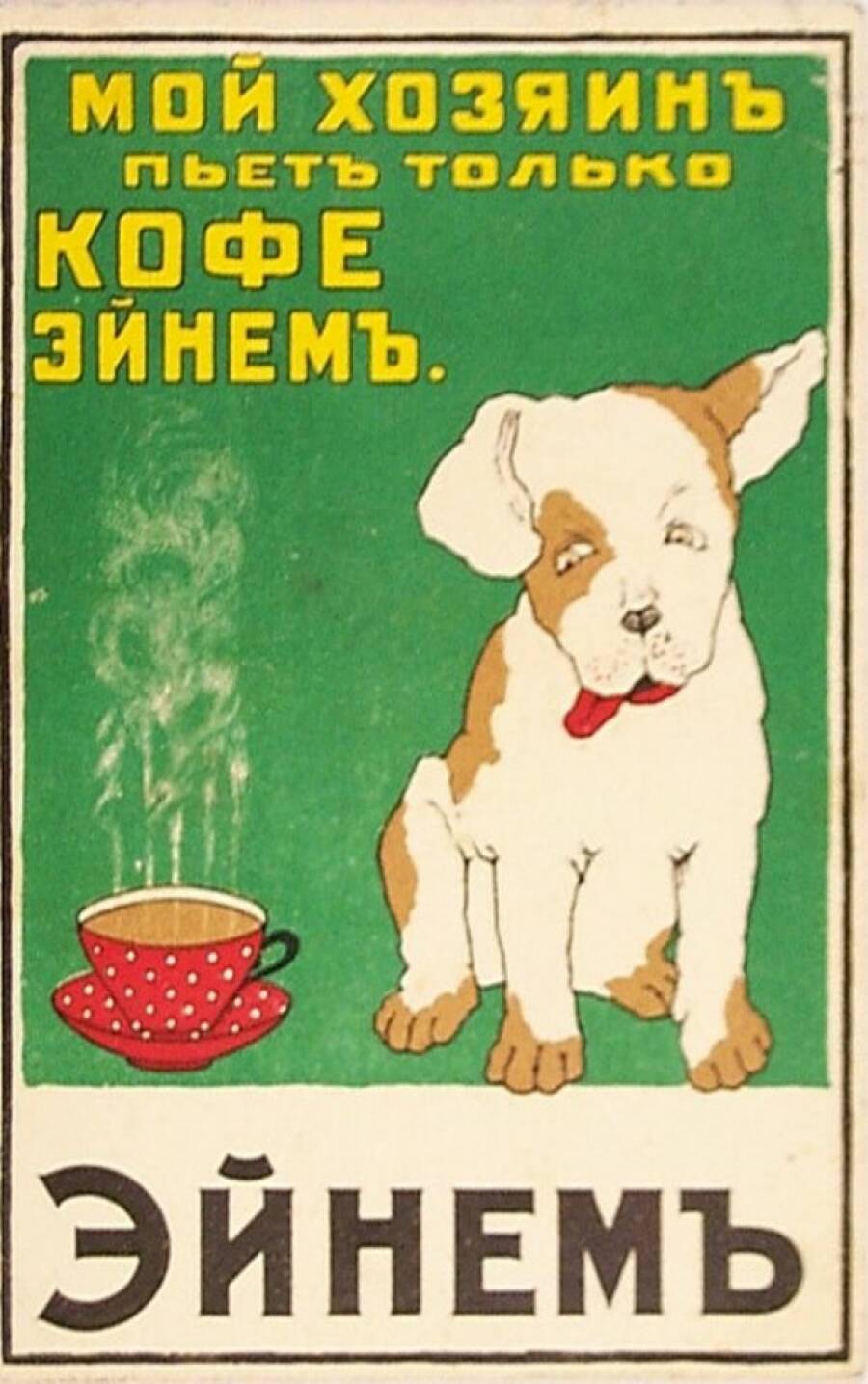

A year before the outbreak of the First World War, coffee imports to Russia amounted to 12 thousand tons per year. The drink became more affordable – one cup in a coffee shop cost two kopecks. However, the war dramatically changed the situation. The government imposes increased duties on luxury, and the elite drink is among the highly taxed products. After the February Revolution, 30 kopecks were already asked for a cup of coffee, and during the Civil War, the drink was almost forgotten altogether. However, there is a cheap alternative – the so-called coffee from acorns. To prepare the drink, the acorns were peeled, sliced, dried on the stove, poured with boiling water, and then fried over low heat. The resulting substance was ground with a coffee grinder and “seasoned” with a pinch of real scarce coffee – for the smell.

Imported coffee returned to Russia during the NEP years, but it was quite expensive. By the 1930s, the cost of a kilogram of grains was eleven rubles, and during the war, the drink again became scarce. A curious episode occurred on the eve of the Victory Day Parade on June 24, 1945. Soviet soldiers recalled that on the night before the parade they were picked up and handed each a glass of coffee for cheerfulness.

The heyday of coffee consumption in the Soviet Union occurred during the Brezhnev period. The Secretary General himself was not averse to starting the morning with a cup of coffee diluted with milk. Then the popularity of the drink increased by one and a half times. Most of the goods came from Brazil, India was in second place, and since 1972, the production of its own instant coffee began in the USSR. Coffee drinks had different names – “Summer”, “Baltic”, “News” – but the composition was about the same. In addition to the coffee beans themselves, they contained chicory, barley and soy. In addition, coffee was sold by weight in grains, packed in paper bags. To date, coffee in our country has defeated tea in the struggle for popularity: a 2019 study showed that Russians choose it almost one and a half times more often.

source :

https://histrf.ru/read/articles/kratkaya-istoriya-kofe-v-rossii-ot-lekarstva-protiv-golovnoy-boli-do-narodnogo-napitka