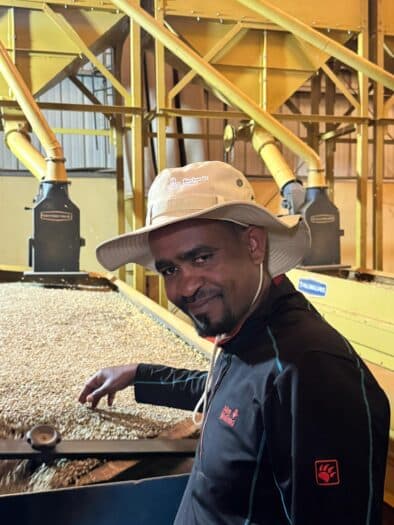

An interview with Musa Kedir CEO, Tourism Attraction and Product Development, Ministry of Tourism – Ethiopia By Qahwa World × Buna Kurs Coffee has long been Ethiopia’s most visible global export, yet its potential as a tourism experience remains largely untapped. While several coffee-producing countries have successfully transformed farms, processing sites, cupping rituals, and café culture

Read More

Sharjah – Ali Alzakary On Maliha Road in Sharjah, where the spirit of authenticity meets the ambition of the future, and golden sands dance with the dreams of a new era, stands “South Roastery” as a true icon in the world of specialty coffee. My destination was not just a routine journalistic visit; it was

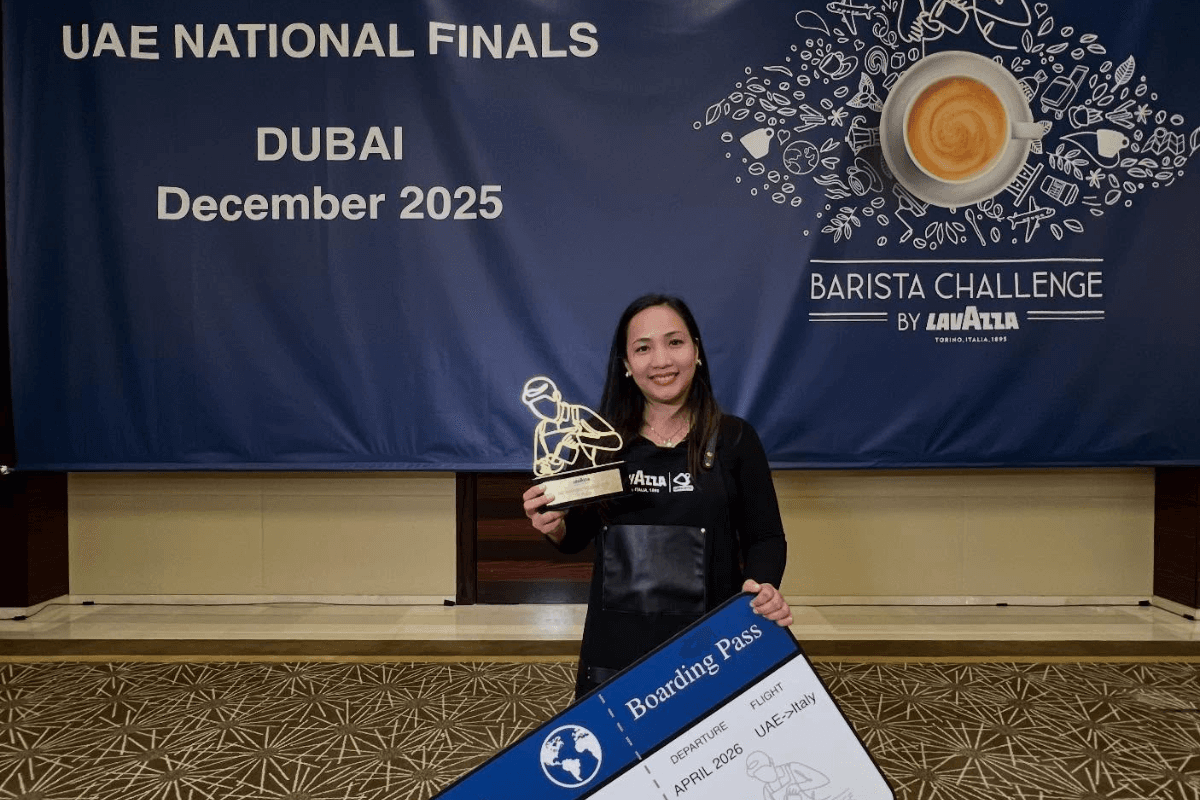

Dubai – Qahwa World Lablibell has been crowned the UAE Lavazza Barista Champion for this year, achieving a well-deserved victory that qualifies her to represent the nation at the Lavazza World Barista Championships in Italy in February 2026. The finals were held on Thursday, December 11th, at the Grosvenor House Hotel in Dubai Marina, where

Dubai – Qahwa World The global coffee market is currently resting in a precarious calm, according to the International Coffee Organization’s (ICO) November 2025 Market Report. Despite major geopolitical and climatic events, the ICO Composite Indicator Price (I-CIP) showed only a marginal rise of 1.2%, averaging 330.44 US cents/lb. This unexpected stability is not a

Moscow – Qahwa World The market for home coffee machines and brewers in Russia saw significant growth during the first nine months of 2025. The number of appliances sold increased by 10% compared to the same period in 2024, reaching approximately 1.7 million units. However, the total market value grew more modestly by 7%, totaling

Dubai – Qahwa World Henrique Braun, currently Chief Operating Officer, is set to become the new CEO of The Coca-Cola Company, succeeding James Quincey, effective 31 March 2026. The leadership transition comes at a critical time for the US beverage giant as it grapples with the future of its Costa Coffee business, which it is

San José, Costa Rica – Qahwa World The Vargas family in Costa Rica has announced the offering of a portion of its long-standing agricultural legacy for sale—the “Finca La Hilda” coffee farm. This estate holds a history that precedes the entry of industry giants like Starbucks into the country, according to a report published by

Minsk, Belarus – Qahwa World Nikita Chakov, the founder of Belarus’s largest coffee shop chain, “Sound,” has unveiled a bold strategy of expansion and radical transformation that threatens to end the traditional role of the “barista” in favour of full automation. In an interview published by the Myfin portal, Chakov confirmed that his network currently

London – Qahwa World Leon, the UK-based food-to-go and coffee chain, has initiated a company voluntary arrangement (CVA) as it works to shut down loss-making branches and reshape the business into a more efficient and sustainable operation. This step follows the recent move by Co-founder John Vincent, who reacquired the brand from Asda just over

Dubai – Qahwa World The global coffee market is currently resting in a precarious calm, according to the International Coffee Organization’s (ICO) November 2025 Market Report. Despite major geopolitical and...

Dubai -Qahwa World The impact of coffee on our nightly rest has long been a fiercely debated topic in scientific circles. However, groundbreaking new research from Swiss scientists at the...

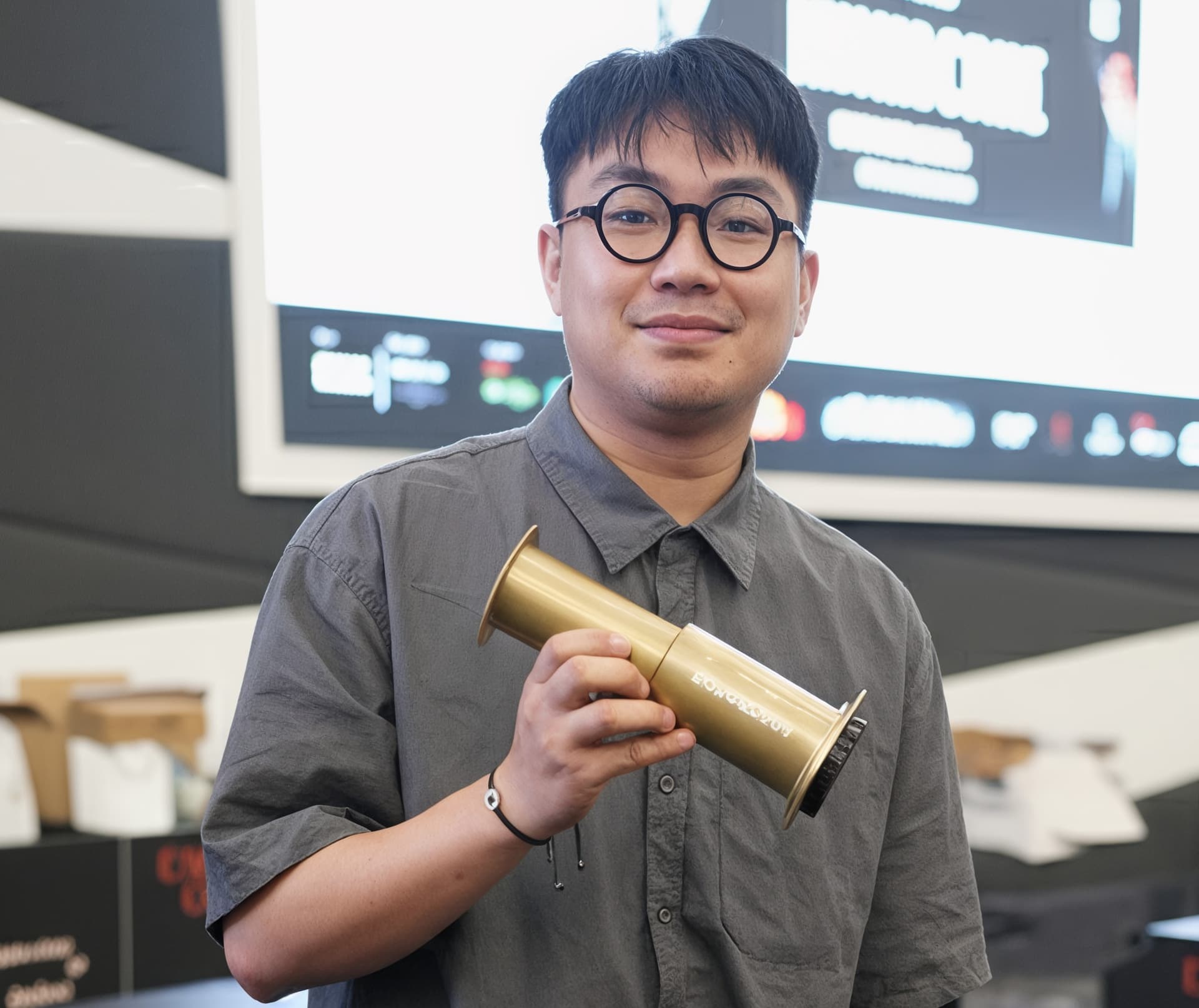

Dubai – Qahwa World A new edition of Project Café East Asia 2026 by World Coffee Portal reveals an exceptional year for the branded coffee chain sector across East Asia,...

Dubai – Qahwa World Multiple Sclerosis (MS), a severe and currently incurable autoimmune disease of the central nervous system, may have a new mitigating factor: coffee. A rigorous systematic review...