Dubai – Qahwa World

Bloomberg published an investigation titled “From Bean to Cup, Colombian Women Push Against Coffee’s Patriarchy”, which stated:

The mist-covered hills of Colombia’s Huila region, lined with dense coffee trees, are witnessing a gradual but determined shift. Women across the country’s renowned coffee sector are stepping into roles once dominated almost entirely by men. They are running farms, forming cooperatives, and launching their own brands, yet deep-rooted gender barriers continue to limit their economic participation—despite historically high coffee prices.

Industry Boom and Leadership Barriers

Colombia’s coffee industry is experiencing one of its strongest periods in decades. Arabica prices reached record levels in October after US tariffs on Brazilian coffee coincided with weak global harvests. Even after the tariffs were reversed, prices remained high, with buyers scrambling to rebuild inventories.

In the twelve months through October, Colombia produced nearly 15 million 60-kg bags of coffee—up 14% from the previous year and the highest level for this time period since 1992, according to the National Federation of Coffee Growers.

Exports rose more than 11% to 13.4 million bags, with roughly 40% headed to the United States.

Women are slowly benefiting from this boom. For the first time in almost a century, they now lead two of the federation’s 15 regional committees. They also represent nearly one-third of Colombia’s 525,000 registered coffee farmers, a rise of more than ten percentage points since the late 1990s. Still, their visibility has not translated into equal access to leadership roles, decision-making power, or financial resources.

- Daily Realities in the Coffee Heartland

In Huila, gender inequality often begins at home. Nery Muñoz, 47, leads a small coffee-growers association in the town of Palestina. Like thousands of women in the region, she manages household responsibilities while working long hours in the fields. “When I have to attend a training session or a meeting, I make sure breakfast, lunch and dinner are ready,” she says. “I also take care of my grandson when my son is working.”

The region also faces the long-term impact of Colombia’s internal conflict and the pressures of illicit crop economies. President Gustavo Petro has encouraged farmers to replace coca with crops such as coffee, but insecurity still affects daily life for many women trying to build sustainable livelihoods.

Cultural Barriers and Financing Challenges

In nearby Pitalito, ten women—including 34-year-old Yineth Sánchez—spent almost a year registering their cooperative, Asoproca. Their goal is to produce and sell coffee under their own brand, but limited legal and technical knowledge slowed progress.

According to adviser Andrea Cano, who works with women entrepreneurs in Huila, deep-rooted gender norms continue to block women from equal participation. “It’s not seen well for a woman to leave her household duties to attend meetings or training,” she says. Many also lack the formal education needed to write proposals or manage projects.

- The Credit Challenge

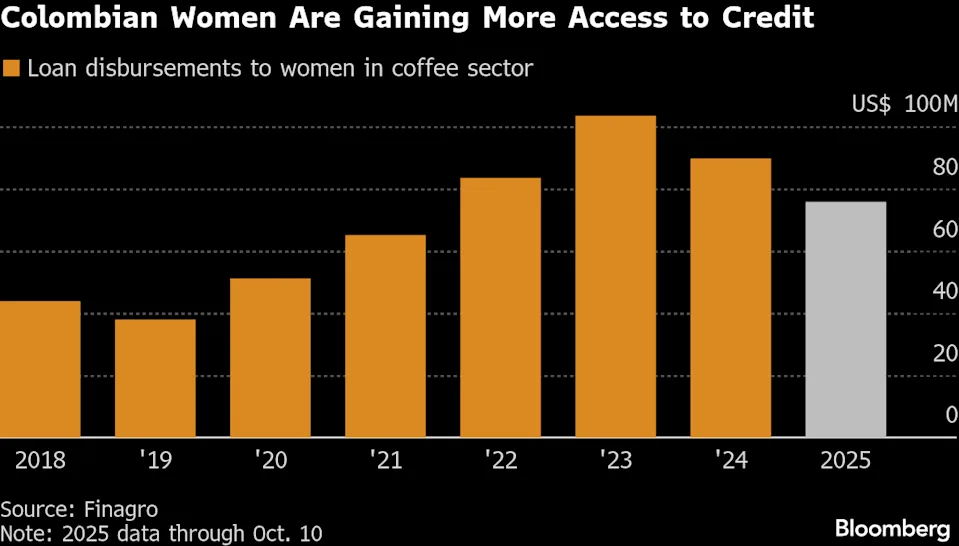

While 51% of Colombians have access to formal credit, the figure drops to 17–20% in rural areas. The gender gap itself is small (18% of rural men versus 16% of rural women have access), but hidden biases and structural barriers make loans harder to secure.

Loan officers often perceive women as riskier borrowers, especially when they lack property titles or appear less confident, says Jaime Rincón of Asobancaria. Yet data shows women have lower delinquency rates on 90-day loans.

Women manage 26% of Colombia’s planted coffee area and produce roughly 25% of national output.

Their farms also tend to be smaller: 59% cultivate under one hectare, compared with 51.2% of male farmers.

- A Year of High Prices—and High Costs

In San Agustín, 44-year-old Edmy Yojana Correa farms 1.5 hectares with her husband, raising 7,450 coffee trees across four varieties. While she avoided chemical fertilizers and earned Rainforest Alliance certification, enabling her to secure higher prices, rising costs for organic fertilizer and labor are squeezing profits.

Edmy sought a private bank loan this year but was rejected. She later secured a small loan from Banco Agrario—about $2,000—after an official from the coffee federation informed her about a financing program she had never heard of. The loan, backed by Finagro, is just enough to fertilize her crops and prepare for next year.

Most women-led cooperatives still struggle to sell their coffee at competitive rates, especially compared with farmers who rely on the federation’s strong logistics and marketing networks.

“Our goal is to export our coffee at a fair price that compensates for all the processing and effort we invest,” says Asmuer leader Blanca Elcy Ome. Yet barriers persist. As global demand for Colombian coffee grows, many women who sustain the industry are still waiting to see the full benefits.

“We do need more support,” Edmy says ahead of a coffee fair in Bogotá. “I know there’s a customer for my coffee. I just have to look for them.”

Gallery