How an ancient hybridisation in East Africa, a handful of historical bottlenecks and a quiet tug-of-war between subgenomes still shape aroma, sweetness, acidity and resilience in modern coffee.

BY: Dr. Steffen Schwarz, Coffee Consulate

If coffee were a person, Coffea arabica would be the one with the complicated family history, the enviable charisma, and an inconvenient vulnerability to illness. It is the species that carries much of the world’s specialty imagination, yet it also carries a biological paradox: despite its global fame, it is genetically narrow. That paradox is not a footnote. It is the plot. And it begins long before the first cup was ever brewed, in a landscape where geology and climate turn evolution into a series of daring gambles: the East African highlands, split and lifted by the Great Rift Valley, with forests expanding and retreating like a living tide.

Arabica is an allotetraploid, which sounds like a technicality until you translate it into something more tangible: it is a natural hybrid that doubled its genome, inheriting two full sets of chromosomes from two different parents. One parent was Coffea eugenioides, a species with a comparatively limited range; the other was Coffea canephora, the widely distributed species that the trade often lumps under the marketing shorthand “Robusta”. Arabica is not merely a midpoint between them. It is a new biological architecture, built from two subgenomes that have had hundreds of thousands of years to learn how to share a single nucleus without tearing each other apart. According to a recent chromosome-level genomic reconstruction, that founding hybridisation and genome-doubling event likely occurred roughly 610,000 to 350,000 years ago, a time window that immediately reframes what “recent” means in coffee evolution.

Imagine what that entails. Two species meet, perhaps in a narrow ecological overlap where altitude, temperature and rainfall allow both to persist. A hybrid forms. In most plant lineages, such hybrids are evolutionary dead-ends, sterile or weak. Yet polyploidy—whole-genome duplication—can rescue fertility by giving chromosomes matching partners in meiosis. In Arabica’s case, the rescue did not come with the genomic chaos one might expect from such a dramatic event. The genomes of the diploid parents and the two Arabica subgenomes are strikingly conserved in structure: chromosome number, broad organisation, even the distribution of genes remains largely comparable, and there is no obvious global “winner” subgenome that dominates expression across the board. In other words, Arabica’s two inherited genomes did not wage a winner-takes-all takeover; they negotiated a long coexistence.

This matters for flavour, because flavour is never just chemistry in isolation; it is chemistry embedded in a living system that decides which genes to turn on, when to turn them on, and how strongly. The genomic work shows that while there is no sweeping, global subgenome expression dominance, there are mosaic patterns within particular gene families—precisely the kinds of gene families that steer cup-relevant traits such as caffeine biosynthesis, terpene formation and fatty-acid desaturation. Some family members are more active from one subgenome, others from the second, and that patchwork differs across development. The bean is, in effect, a stitched fabric of inherited programmes.

To connect this to the cup, it helps to stop treating genetics as destiny and start treating it as a set of probabilities. Genes do not taste like anything. But genes encode enzymes, and enzymes sculpt the pools of molecules that later become aroma, taste and mouthfeel—directly, or via roasting transformations, or via fermentation dynamics that the plant’s chemistry invites. In Arabica, the gene families highlighted in the genomic study offer a particularly clear bridge from inheritance to sensory line: N-methyltransferases involved in caffeine biosynthesis, terpene synthases associated with volatile terpenoids, and fatty acid desaturase 2 linked to unsaturated fatty acids.

Caffeine is the easiest to mythologise and the hardest to simplify. It is often framed as a single scalar—more or less stimulation—yet from the plant’s perspective caffeine is a defence molecule, part of a chemical conversation with insects, fungi and competing plants. The enzymes that methylate xanthosine derivatives stepwise towards caffeine are encoded in a family of related genes, and in Arabica the presence of two parental subgenomes means extra copies exist, with expression patterns that can differ during fruit development. The sensory implications go beyond “bitterness”. Caffeine contributes bitterness, yes, but its perceived intensity depends on concentration, matrix effects, extraction, and the balancing counterweights of sweetness, acidity and aroma. In a world where consumers increasingly chase brightness and clarity, the genetic architecture behind caffeine becomes a quiet partner in how far roasting and brewing can push without tipping the cup into harshness.

Terpenes, by contrast, are the aromatic storytellers. They can read as floral, citrus, herbal, resinous, sometimes minty or spicy, and they often act at extremely low concentrations. The terpene synthase family is large and versatile, and in Arabica its expression is again mosaic, with contributions from both subgenomes. This helps explain why certain lineages and certain origins can feel as though they possess a genetic “accent” that processing and roasting can amplify but rarely invent from scratch. When a Gesha cup throws jasmine, bergamot and ripe stone fruit across the room, it is not only terroir and craft; it is also a set of inherited catalytic potentials that make particular volatile pathways easier to access.

Then there are lipids—often overlooked by managers until a defect complaint arrives, yet essential to quality perception. Fatty acids influence mouthfeel directly, and they influence aroma indirectly by shaping the reservoir of precursors and the physical behaviour of volatiles during brewing: how they partition, how they linger, how they ride the crema or vanish. Fatty acid desaturase activity shifts the balance between saturated and unsaturated components, which in turn influences fluidity in biological membranes and the lipid profile stored in the seed. Again, Arabica’s two-subgenome nature provides extra copies and potentially divergent regulation.

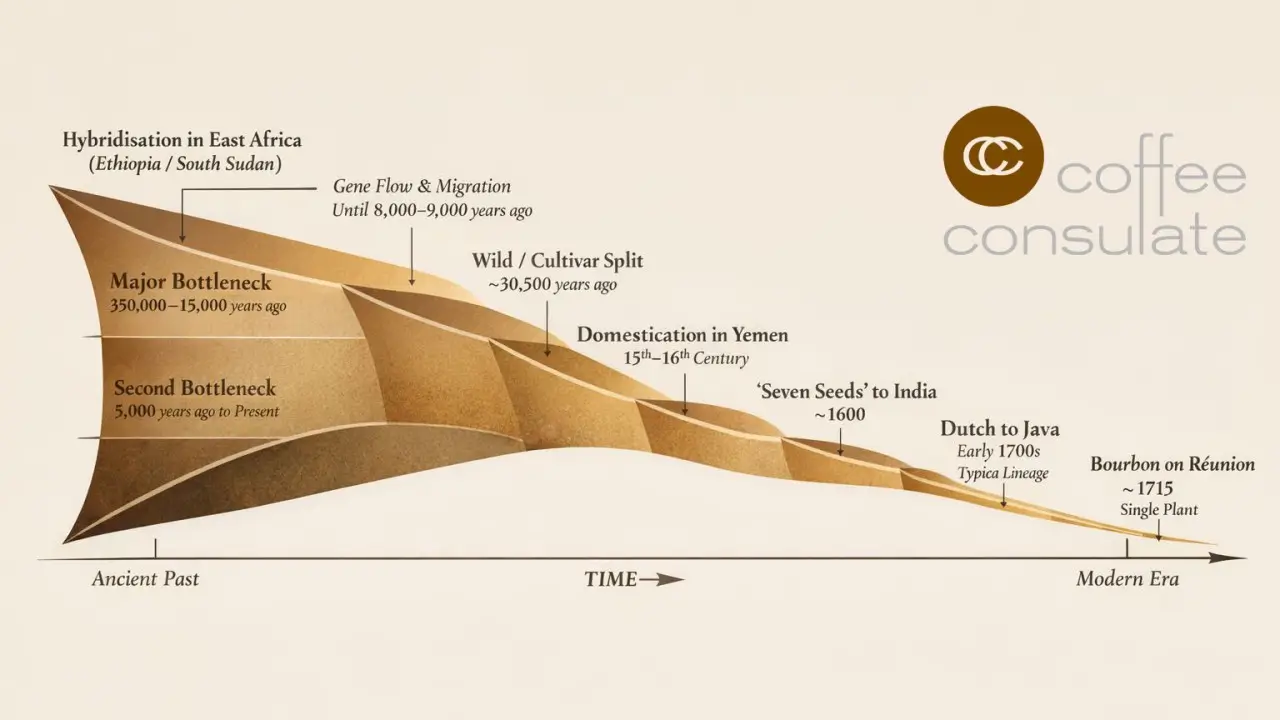

So Arabica’s sensory richness is, at least in part, a polyploid dividend: not because the genome doubled and instantly created “better flavour”, but because doubling created redundancy, and redundancy allowed fine-tuning. Yet this same evolutionary path came with a steep cost: an astonishing series of bottlenecks that squeezed diversity long before humans ever selected a tree. The genomic reconstruction identifies a major bottleneck beginning around 350,000 years ago, lasting until roughly 15,000 years ago, when climatic conditions improved at the start of the African humid period. A second, more recent bottleneck began around 5,000 years ago and persists to the present in wild populations. If you are responsible for a supply chain, this is not abstract history. Bottlenecks mean limited adaptive capacity. They mean fewer alleles to draw upon when temperatures rise, pests spread, or rainfall patterns shift.

The story then tightens further. Within Arabica, the split between the wild population and the lineage that would seed modern cultivars is estimated at around 30,500 years ago, followed by thousands of years during which the two populations still exchanged genes—migration continuing until roughly 8,000–9,000 years ago. This is a remarkable insight because it suggests that “wild” and “cultivar progenitor” were not cleanly separated worlds; they were neighbours, trading alleles across a landscape that may have included both sides of the Great Rift Valley. It also opens a provocative possibility raised by the authors: that the end of migration might align with rising sea levels and the widening of the Bab al-Mandab strait between Africa and Yemen, severing a corridor that could once have been narrower or even intermittently passable.

That brings us to the human chapter, which is often told as romance and smuggling but is better understood as another bottleneck layered on top of biological fragility. Arabica cultivation was initiated in fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Yemen, and the cultivated world that followed was built on astonishingly few founders. Around 1600, a tiny cache remembered in lore as the “seven seeds” left Yemen and established Indian lineages. A century later, Dutch cultivation in Southeast Asia set up the founders of the contemporary Typica group, while French cultivation on Bourbon (Réunion) descended from a single surviving plant, forming the Bourbon group. It is difficult to overstate what this means: much of what the world calls “classic Arabica quality” is the sensory expression of a genetic narrowness that survived by luck, logistics and human preference.

From a sensory standpoint, those historical funnels did something else: they created coherent flavour lineages. When roasters describe Bourbon as “sweet, rounded, balanced” and Typica as “clean, elegant, sometimes brighter”, they are often drawing from thousands of sensory memories. But those memories may be tracing, indirectly, the consequence of founder effects—of which alleles happened to survive Yemen, the “seven seeds”, the greenhouse in Amsterdam, the ship to the Caribbean, the single plant on Bourbon island. These are not merely travel anecdotes. They are genetic filters that altered the available palette of enzymes, the ratio of subgenome contributions, and the likelihood that certain aromatic or metabolic pathways are robust under stress.

And stress is the recurring antagonist. Arabica’s narrow diversity makes it susceptible to pests and diseases, most notoriously coffee leaf rust, Hemileia vastatrix. In the early twentieth century, a spontaneous hybrid between Canephora and Arabica was identified on Timor in 1927, resistant to leaf rust, and it became one of the most consequential genetic events in modern coffee breeding. The industry often narrates this as a rescue story—and it is—but every rescue comes with trade-offs. Introgressions from Canephora can deliver resistance, yet they have also been associated with unwanted side effects, including decreased beverage quality.

Here, genomics adds resolution to what cuppers have long suspected. The study shows that introgression in Timor-hybrid-derived lines occurred almost exclusively within the Canephora-derived subgenome portion of Arabica (the subgenome inherited from Canephora), forming large genomic blocks that can cover roughly 7–11% of the genome in those lines. These are not subtle single-gene edits; they are sizeable inherited segments, young enough in evolutionary terms that recombination has not yet broken them into fine-grained fragments. When a breeder says “this cultivar has Timor”, genomics clarifies what that means: there are substantial regions where the flavour-relevant metabolic background may also shift, because resistance does not arrive alone.

The resistance locus on one chromosome region contains clusters of genes associated with immune responses—homologues of known resistance-related families, including arrays of genes analogous to RPP8-like resistance loci, regulators such as CPR1 homologues, and kinase families linked to rust resistance in other crops. Even without turning this into a catalogue, the principle is clear: disease resistance often involves gene clusters, duplication, and regulatory networks that can be metabolically expensive or pleiotropic. A plant that holds the immune system on a tighter trigger may allocate resources differently during seed development, and those reallocations can ripple into bean chemistry. That does not doom quality; it reframes quality management as a multi-variable optimisation problem rather than a moral judgement about “good genetics” and “bad genetics”.

Yet Arabica’s genome has another, subtler generator of variation: homoeologous exchange, a process where the two subgenomes occasionally swap segments. Arabica generally behaves with disomic inheritance, pairing homologous chromosomes as if it were diploid, but because the subgenomes are similar, occasional exchanges can occur. The study finds remarkably concordant exchange patterns shared across wild and cultivated Arabicas, including a fixed bias at one end of chromosome 7 toward the eugenioides-derived subgenome, possibly selected to maintain compatibility between nuclear genes and the eugenioides-derived chloroplast genome. In plain terms, Arabica may have edited itself early on to ensure that the nuclear instructions match the chloroplast machinery—an invisible compatibility fix that helped the hybrid persist.

More intriguingly, the work reports a broad bias in many accessions toward allele ratios favouring the Canephora-derived subgenome in other regions, with the authors suggesting that, in a low-diversity polyploid such as Arabica, homoeologous exchange could be a major contributor to phenotypic variation among closely related accessions. This is a powerful idea for anyone trying to reconcile the paradox of Arabica: how can something so genetically narrow still show such sensory diversity across origins and cultivars? Part of the answer may be that the genome is not static even when diversity is low; it can reshuffle inherited components between subgenomes, generating new expression mosaics without needing vast numbers of new mutations.

Now, add geography. The genomic sampling of wild and cultivated accessions points to a split along the Eastern versus Western sides of the Great Rift Valley, with cultivated variants placed with the Eastern population. Wild accessions from the Gesha region appear as a hotspot of material genetically close to the hypothetical wild parent of cultivated Arabica, with admixed individuals acting as intermediates. This gives the Gesha name a deeper resonance: not only a modern sensory icon, but also a geographical node in Arabica’s pre-domestication genetic landscape. When the market pays extraordinary premiums for Gesha, it is responding to a sensory signature that may reflect ancient admixture and a particular arrangement of inherited metabolic capacities, preserved through historical chance and then amplified through contemporary selection.

All of this leads to an uncomfortable, practical conclusion: Arabica’s global success was built on a very small evolutionary and historical foundation, and that foundation is being asked to hold more weight than ever before. Climate change is not merely a yield problem; it is a flavour stability problem. Heat alters bean development speed, shifting sugar accumulation, organic acid balance and volatile precursor formation. Pathogen pressure alters plant allocation and can force breeders toward introgressed resistance that may, depending on how it is managed, reshape cup profiles. And the industry’s traditional approach—treating genetics as background and processing as foreground—becomes increasingly risky when the background is this constrained.

The genomics does not tell us that “Bourbon tastes like X because of gene Y”. That level of determinism is neither scientifically fair nor operationally useful. What it does offer is a map of constraints and opportunities. It shows that Arabica’s two subgenomes coexist without obvious global dominance, yet within key metabolic gene families the contributions are patchy and dynamic. It shows that population history includes multiple bottlenecks that explain why modern diversity is low even in wild accessions. It shows that the domestication pathway did not begin from a broad, diverse wild pool but from an already squeezed lineage, and that the spread through Yemen and beyond introduced further founder events that shaped today’s cultivar landscape. It shows that resistance introgression is, at genomic scale, substantial and structured, not a tiny adjustment. And it suggests that homoeologous exchange may provide an internal engine of variation, perhaps one of the few available in a species where classic diversity is scarce.

For decision-makers, the sensory implication is not that we should fear genetics, but that we should manage it with the same seriousness we apply to roasting curves, fermentation protocols or equipment calibration. If a cultivar’s aromatic potential is partly a consequence of terpene synthase family expression mosaics, then agronomy and post-harvest handling become the arts of revealing that potential rather than manufacturing it. If caffeine pathway genes and lipid profiles vary subtly across lineages and introgressed backgrounds, then extraction and roast development should be tuned with a clearer awareness that “Arabica” is not one chemical template. If disease resistance is delivered through large introgressed blocks, then quality evaluation should shift from binary judgements (“Timor tastes bad”) to structured sensory and chemical profiling that identifies which blocks, which backgrounds and which environments can carry resistance without sacrificing cup character.

And for those of us who teach coffee, this story offers something even more valuable than facts: it offers a narrative that is scientifically grounded yet emotionally legible. Every cup becomes an archaeological artefact. The sweetness in a Bourbon is, in part, the echo of a single plant surviving on an island. The clean clarity of a Typica lineage is, in part, a botanical passport stamped in Yemen, India, Java, Amsterdam, the Caribbean. The jasmine lift of a Gesha is, in part, an ancient genetic conversation across the Rift Valley. The resilience of a rust-resistant cultivar is, in part, a young block of Canephora-derived genome riding inside Arabica’s elegant but fragile architecture. And the entire edifice rests on a rare evolutionary event—two genomes choosing coexistence over conflict—followed by a chain of bottlenecks that should, by rights, have narrowed possibility to near silence, yet somehow still left enough space for complexity, beauty and surprise.

There is a final twist, and it is perhaps the most sobering. The same genomic work that celebrates Arabica’s harmonious subgenome coexistence also underlines how perilously thin the margin is. In a future of higher temperatures, shifting rain, expanding pest ranges and increased market volatility, the industry will not be saved by nostalgia for classic lineages alone. It will be saved by an applied science mindset: using genomic tools to understand heritage, using breeding and selection to widen adaptive capacity, and using sensory science to ensure that resilience does not mean the end of delight. Arabica was born from an improbable hybridisation and survived through improbable human history. Our task now is to ensure that improbability does not run out.